David Lerner expected poetry to save the world. He expected this quite literally and concretely. He expected both to change the culture around him , and to change his own position in life. He expected poetry to reawaken the primacy of feeling in modern life like some dormant gland. He expected poets to take the helm of modern culture, and steer us toward a future where the human soul is restored of meaning. A wild, impractical dream, perhaps, but let me not live in a world where such a dream is only madness.

David Lerner expected poetry to save the world. He expected this quite literally and concretely. He expected both to change the culture around him , and to change his own position in life. He expected poetry to reawaken the primacy of feeling in modern life like some dormant gland. He expected poets to take the helm of modern culture, and steer us toward a future where the human soul is restored of meaning. A wild, impractical dream, perhaps, but let me not live in a world where such a dream is only madness.

Lerner gave everything to his poetry, even to the point of madness. He sought, through poems, to re-balance the contradictions of power and feeling that warp modern life. Lerner was a rebel, in both the best and worst sense. He refused to accept the inhumanity that rules society, and insisted the world adapt itself to his vision of truth, of justice. Any five year old learns the world doesn’t work this way, but Lerner was not just anyone. He had a genius for exposing the web of impossible lies which rule just beneath the surface, and showing them for the carnal growls of the beast in man. He did this in poetry-compelling images rung clear as a bell, well-honed lines, a unique poetic style which draws us in through humor, then works on the conscience like a corrosive acid.

Lerner was a sort of modern prophet, the sort that perhaps the modern world deserves. Hassled, over-burdened, consumed by the culture of consumption, hounded by money and haunted by the flood of soulless images which assault our feeling selves, Lerner wrote with fury to change the world. Like his idol, the poete maudit Arthur Rimbaud, Lerner expected impossible things from poetry, and many of the burdens of his life resulted from that. He put himself in an impossible circumstance, attempting unsuccessfully to bring his vision to society through songs, journalism, fiction, publishing, and any medium that might sustain him while allowing him to remain true. He was constitutionally incapable of compromising his vision. Much of the best of what Lerner has to offer is still buried in his letters and his life. Lerner’s response to the impossibilities of this life was to quote Rimbaud: “I am of the tribe that sang under torture.”

And sing he did. Though there have been only four books to date, thousands of pages of fascinating unpublished material was found in his apartment at the time of his death. Entire poetic styles which he had nurtured and mastered were evident, none of which were released during his lifetime. In addition, Lerner was a master letter writer, and produced another thousand pages of touching personal correspondence on art, literature, life. This material has been lovingly preserved through the efforts of his friends and literary executors.

From the early 1960 s David was a member at large of the Fort Hill Community, returning periodically to rest, rehabilitate, re-focus, play music, sing. The group was a stable influence on him in unstable times, particularly his close friendship with Jessie Benton, daughter of the classical American painter Thomas Hart Benton, and George Peper, head of the Fort Hill Construction Company. David felt that his poems would be forever cared for, his memory endure in the hands and heart of his extended family. And so it did. I have read in this archive for hours, and it contains a fullness and depth that surpasses even that mix of humor and vision which made Lerner a poetry phenomenon in mid-1980s spoken word San Francisco.

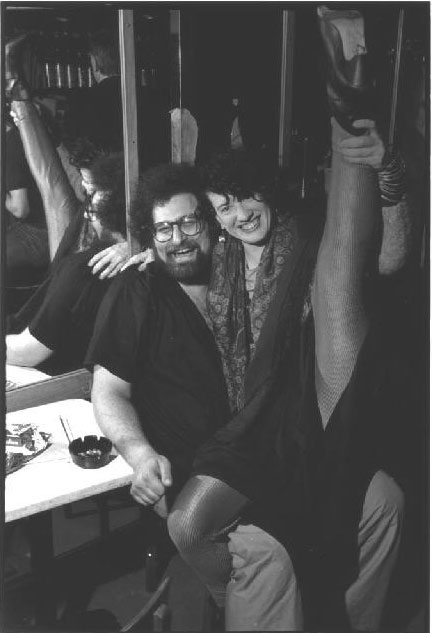

In his own life (1951-1997), Lerner, sacrificed all for his dream. Tall, 6’4″, with a gut and big hair, Lerner was both flint and steel for the flame which consumed him. He was all contradiction, child and monster, bombast and buddy, prince and beggar, he wanted, he once said, to carry himself like the king of a ruined but noble nation. Early on, when I met him, he had thrown over a book advance, resulting from syndicated articles, to pursue his poetry. He’d also given up a moderately successful journalism career because it interfered with the poetry. As his economic situation became more desperate, he became even more committed to the poetry, to his plans for changing the world. It would be easy to say that this was madness, and indeed there were times when he harvested his own biochemical imbalance like a spring lamb laid on the altar of art. But to know and love David, as I did, was to understand that this was his choice for life, as well as death. He didn’t court ruin, but who he was, and chose to be, placed him in the grips of a dream merciful as a hangman’s noose. He lived and died entirely devoted to that dream. When has the world made room for such a one?

As a friend, Lerner could be impossible to handle. But he also saw and honored the most fragile part in each of us. He only knew how to love absolutely, and love he did, forthrightly, desperately, with quiet fury and an unmatched private intensity. His wife, Maura O’Connor, in a poem, once described “His Heart and All the Messy Places He Put It.” There was no tragic intent. He wanted to live. He wanted to flourish. He wanted inconsolably to bring the dream of poetry to a people that couldn’t yet see it. But he lived with poverty and drugs, incarceration and madness. But David Lerner is not so easily dismissed by his worst self. He is entitled, as any poet, to be judged by his best. And his best is exceedingly good: funny, perceptive, endlessly appreciative of beauty, he made a faith of the pure truth of feeling. His images shine with instant, intuitive recognition. The mission of poetry, he once said, is to “drive a cherry-red Mercedes Benz into the heart of hell and place a bet on God.”

This he did, and he relied on us, today, readers and friends, to carry that bet this last mile. It is here, in this book, his bet on “the red, white and blue, its measureless promise boiled down to a dollar, for women who’ve never been touched, and for men who don’t know how…” For David Lerner, poetry meant everything. His was a rave for beauty, a scream for sanity, a mad laughing monologue to convince us to honor the eternal in our selves. Are you listening?

-Bruce Isaacson, Las Vegas, Nevada