David Lerner, Bruce Isaacson, Julia Vinograd, Daniel McColgin, David Gollub

This is a history and overview of our past, and a vision for our future.

For information about submitting work, please go to our Your Manuscript page.

David Lerner, Bruce Isaacson, Julia Vinograd, Daniel McColgin, David Gollub

This is a history and overview of our past, and a vision for our future.

For information about submitting work, please go to our Your Manuscript page.

Zeitgeist Press started in 1986 to publish work from a group of poets generating tremendous heat at the Cafe Babar readings in San Francisco. It was originally a collective more than a traditionally structured press, which explains both the press strengths and weaknesses.

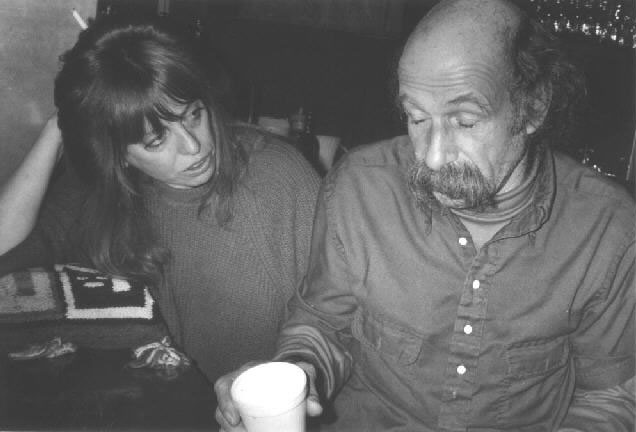

Alvin Stillman and Laura Conway. Photo by Richard Gibson.

All the way back to the late 1950s North Beach Coffee Gallery, there was a Thursday night open reading in San Francisco. This community spawned some incredible poets– Bob Kaufman, Richard Brautigan, Jack Micheline. Other top poets of the era passed through as well– Diane di Prima, Ginsberg first drafted Howl at a cubbyhole in North Beach, Jack Gilbert, Corso & Kerouac, Rexroth, Ferlinghetti, etc. The reading had died down, lost energy, by the mid-1980s when it moved to the Mission District in 1985.

Bruce Isaacson and David Lerner were the original partners in the 4 books that came out on Zeitgeist Press at the end of 1987. Lerner named the press and did publicity. Isaacson handled the business side, the mechanics, and acted as publisher. Both edited books by various authors, as did poets Julia Vinograd, Bana Witt, and others.

One of Lerner’s pithier publicity slogans was “Poetry you can actually read.” This reflected the frustration of this group of urban poet-kids with the mainstream or academic poetry of that era, which seemed obtuse, or so pasteurized as to be irrelevant to the reality of their urban lives. This idea, along with a burning for poetry that mattered in society, was reflected in anthems such as Lerner’s Mein Kampf. And there was, in that era, little room for humor in the hubris that sometimes passed as high art. By now, that’s changed in today’s mainstream poetry. Back then, the Zeitgeist crew wanted something different. They wanted a poetics that was direct, and not just directed at poets. They wanted something that would make a difference generally in the way people felt. They wanted something more proletarian, more relevant to street life, as lived by all these intense poet-eyes wandering the Mission District of San Francisco. They wanted something ordinary people, or artists working in other art forms, could pick up and read, that would resonate with them without any insider’s mystery as to what had been said. Something that would affect the world, help it evolve toward a more sentient and true inner life. Something that would at least stand in opposition to the marketing-driven, advertising-designed aesthetic that dominates the culture at-large.

David Lerner and Anna Wolfe. This was also seen on the back cover of his book “I Want A New Gun”. Photo by Richard Gibson.

So an influx of new poets flamed up with amazing intensity in the readings and this group of young poets found a way to develop their craft in the back room at Cafe Babar. Alvin Stillman owned the place, and made it all possible. The room was only about 30′ x 30′, with wood bleachers and corrugated aluminum siding stretched over the walls. At critical points, the poet could hit the walls and the entire small room would vibrate. Often, there were 75-100 people stuffed in shoulder-to-shoulder, crowding the halls and every spare inch of space, hungry for what the poet could do? make the crowd laugh, or burn with rage, or just give some true feeling in any of the myriad ways poems can touch people.

And that crowd was merciless. There was no nicety, no polite applause, no tepid response. If they loved you, they were delirious with applause and appreciation. And if they didn’t, the poet might get hoots, whistles, the audience would talk back, yelling clever criticisms in the middle of long bad poems, or worse, beer glasses would sometimes fly towards the stage.

It might take a poet 2-3 years to sort through their own mental bullshit before being able to write things that started to reach people. There were so many failed poems, so many poets striving to hear their own voice. But many were determined, and that’s what was needed. The Babar was not a place for the overly-sensitive poets, but it was a great place to learn your chops, to learn the difference between what might actually touch people and your own self-important crap. After going through that fire by trial, a lot of the poets came out of the experience pretty damned sure of who they were, and what they had to say. So, that was the Babar.

Lerner died in 1997, but his literary executors, the so-called Lyman family, help the press in establishing its 21st century resurgence. They published Avatar, the underground psychedelic paper from Boston in the 60’s, then moved to LA and today run a construction business, building compounds for movie stars. But they have a long background in the arts, including the remaining family of Thomas Hart Benton, the classic American painter, whose grandfather JFK wrote about in Profiles in Courage. So they’re really part of the classic American arts world, and have supported Zeitgeist significantly.

Julia Vinograd, who was just named Poet Laureate of Berkeley by the city council, is also a key person in the press. Julia’s poems represent street life with humor, intelligence, and skill. She earned an MFA at the famed Iowa Writers Workshop. But she really identifies with the street life of Telegraph Avenue, and has put a couple hundred thousand books in print selling them one hand at a time on the streets of Berkeley.

In Las Vegas, Harry Fagel, the police officer and poet has just finished his second book on Zeitgeist, Undercover. His in-your-face, hard hitting urban style matches the earlier Zeitgeist ethos in a lot of ways.

But Zeitgeist poetry was never all bad mouth and bluster. Some of the work Zeitgeist published was funny, or just plain fun, and some was angry, reflecting the trials of AIDS and homelessness and drug violence. Zeitgeist will release a CD in 2005 by Eli Coppola, whose work manages to be both unbelievably strong and tenderly fragile at the same time. Eli was one of Zeitgeist’s best poets, she had muscular dystrophy and passed away very young in 2000.

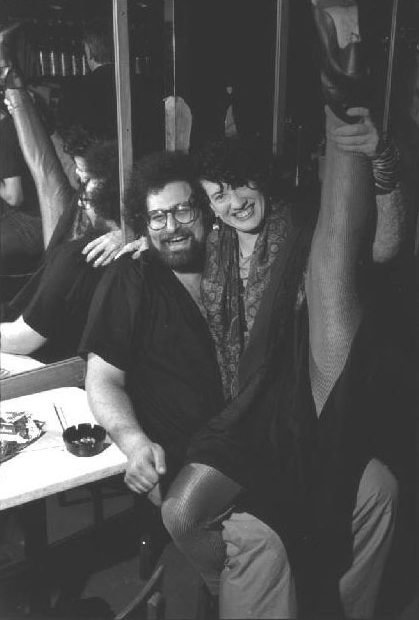

Danielle Willis and David Lerner, front room of Cafe Babar. Photo by Richard Gibson.

Another key poet, Laura Conway, a sort of Whitmanesque hypnotist, sought a vision to synthesize and explain the whole world from the perspective of poetry. She emigrated to Prague in ’94 or ’95 and has been living in the Czech Republic for over a decade now. And there’s no minimizing the influence of the whole group of Zeitgeist writers, including Kathleen Wood, the incredible muse and poet of unflinching honesty, firebrand Joie Cook, jazz-poetry-great Q.R. Hand, SF’s internationally famed Jack Hirschman, New York essayist Jennifer Blowdryer, brilliant satanic humorists such as Danielle, Willis, Vampyre Mike Kassel, or extraordinary poets of the underside of society such as Sparrow 13, David Gollub, and David West,

Zeitgeist sought to publish poets who could reach people who were not poets, sought to reconnect the art form with its base of readers, and to make a place for a new, edgier, younger group of urban poets who were questioning the ordering of society, the ghosting of the soul in modern life, and the relegation of direct truthful speech to a raving societal sideshow.

David Lerner, in particular, wanted to use modern poetry to change the world. His own poetry could be described as an assault–using humor, poignant empathy, sharp metaphor and anger, as weapon against that initial corruption of the heart that is the foundation of most evil done in society. He was no mahatma, heaven knows, but his poetry sought that kind of moral influence on modern American culture. There hasn’t been another poet quite like him, and his goal for poetry made Zeitgeist Press unique. His Selected Works, The Last Five Miles to Grace, is due out in spring 2005.

Most all of the people Zeitgeist published could be described as underclass. Zeitgeist poets made their livings as stringers and strippers, some were on SSI and others worked marginal blue collar jobs, house painters, waiters, bartenders. Zeitgeist didn’t publish a single person at that time who made a living teaching, not because they were excluded, but they generally preferred the captive house of the classroom to the raucous madness that prevailed at Babar. Since then, we’ve found out there were numerous people in various PhD and MA programs at Berkeley and SF State who were sitting in the bleachers at Babar, people who became prominent poetry teachers and intellectuals, like Tony Barnstone (Whittier College), Justin Chin, Jeffrey McDaniel (Sarah Lawrence College), and others…. We also had our share of punkers who checked it out, like Lydia Lunch. East Bay Ray hung out, the guitarist from the Dead Kennedys. One of our poets, Bana Witt, was fronting Ray’s new band and engaged in various wildnesses with Artie Mitchell and Hunter Thompson at the same time. You had to love the melee, the anarchy, to come back repeatedly, so the people Zeitgeist ended up publishing were pretty different from those typically published by small presses and academic institutions in those years.

Cafe Babar front room in the evening. Visible are Anna Wolfe, David Lerner (right) and Alvin Stillman (proprietor, who as Lerner once wrote, “…will surely be a saint in heaven, as he is now in hell).” Photo by Richard Gibson.

Still Zeitgeist poets loved many academics, and wanted to learn. Several took classes at UC Extension from Richie Silberg of Poetry Flash, Eli Coppola studied with June Jordan at Berkeley, and Bruce Isaacson went to considerable trouble to get into classes from Robert Hass, Allen Ginsberg and others. Popular music was more important than intellectuals to some of the Babarians-Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Tom Waits. Some of the key influences were “teachers” from the old North Beach scene, which was really very intelligent, not at all the bohemian no-nothings portrayed by the media.

Some important North Beachers actively hung out and “taught” in the cafes and bars of the Mission, and tutored younger poets in very practical ways. We remember Jack Micheline, especially, who had already been the most famous poet in SF in the 1970s, and helped several Zeitgeist poets. If you asked him about publishing your work, he’d launch off on a tirade about standing up on the pool tables of bars to show the people some genuine spirit. That attitude and example helped push us past the notion of sitting back and waiting for some mythical Ferlinghetti to come along and publish us. It got Zeitgeist going on its own.

Jack Hirschman, who had been a tenured Professor at UCLA and taught at Dartmouth while Bruce Isaacson was there, was important. Jack was a serious radical and hated the Babar at first for being insufficiently political. But as the scene matured, he found things he liked. He’s still one of the foremost translators for poetry in America. His reach to other cultures helped give Zeitgeist poets better vision. After Isaacson traveled to Russia, Hirschman’s broader reach and aspiration started making sense.

Andy Clausen was a very important influence in terms of connecting the Babar scene up with the old Beat scene in New York and San Francisco. He’s a spectacular reader, and participated in a lot of the readings. He and Isaacson sponsored a series of Poetry Meltdowns, a sort of “poetry cabaret” that made the performance fun. These people, from the North Beach Beat scene, were there as examples and teachers to anyone willing to seek them out, as quite a few younger poets did.

Gregory Corso was very important, both in his example of the bad-boy street theatre that was his life, and in the careful thought, mixed abundantly with humor and performance, that was in his great poems. Corso’s poem “Marriage,” for example, was the first of its type– it could go both ways, both work as a performance script and in the classroom as a serious criticism of the individual’s role in society. He would stop by the readings, or come stirring things up in North Beach. He was a jokester and truth-teller, very brave, a sort of holy fool, and vagrant, and he influenced younger poets a lot. There was a “half act” play by Donny Grose, called “Gregory Corso’s Bed.” It had no actors and opened to a spotlight and blank stage.

Corso remains under-appreciated even within the Beat scene. His book Elegiac Feelings American, written on the death of Jack Kerouac in the late 1960s, forms a bookend with poems like Howl or even better–Kenneth Rexroth’s “Thou Shalt Not Kill” elegy on the death of Dylan Thomas. These may be the poems that define the era. Much as the era of Romantic poetry in England begins with the publication of Lyrical Ballads and ends with the death of John Keats, and “Adonais,” Shelley’s great elegy for Keats. Corso’s elegy may mark the end of an era in which poetry had a more direct impact on American society than it ever has. In the arts, this may be remembered as the Beat era, bringing on the changes of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. Society followed the expansion of social mores, lifestyles and thought that it discovered in Beat poetry, in Corso’s poetry. There aren’t many poetry movements that have set off that kind of broad cultural change.

Stylistically, Bob Kaufman, widely known overseas as the Black American Rimbaud, was a huge influence. In particular, his great New Directions book Solitudes Crowded with Loneliness was like a bible to the Mission St. poets. There you have both poems of incredible humor like the “Abomunist Manifesto,” mixed in with poems of deep feeling and lyrical genius like “Image of Wind”, “Afterwards They Shall Dance,” and “For Parker Asleep in the Next Room.” He also wrote poems of social criticism, like the book length Golden Sardines about reintroduction of the death penalty in 1960 and the execution of Carl Chessman, though it’s primarily a surrealist bouffe-“a movie shot with the eyes” he called it. And there was his poem for Crispus Attucks, foreshadowing the re-writing of American history that became multi-culturalism. And not just on racial issues– Kaufman was of mixed parentage, Black and Jew–but he was also important in the gay community as you could see in his poem great poem “Ginsberg” and “Grandfather Was Queer Too”. He is arguably the most important American surrealist poet, with graceful, lyrical images that stand the test of time mixed with a sort of strolling jokesterism than hasn’t been achieved since Appollinaire. So there’s a great black American poet of genius and conscience that remains unassimilated by the poetry establishment in America.

Julia Vinograd is perhaps Zeitgeist’s best-known poet, and has received awards and recognition that reflect a substantial achievement. She does a number of things that people respond to. Julia’s poetry humanizes the bottom rung in the social ladder, and not with pathos or bathos, but revealing basic human motivations and circumstances that all of us relate to. Julia doesn’t glorify poorer people or make them into some sort of proletarian concept, they’re just people, and she manages to express the range of foibles and nobilities equally. In these times, there is perhaps nothing more relevant than to spread empathy across socio-economic lines.

Julia Vinograd as seen on the cover of her book “Ask a Mask”.

Julia’s work is also a wonderful, oral history of one of America’s great artistic cities from the 1960s through today. It’s tremendously entertaining, and defines her place and time like Damon Runyon did for Broadway, or Bukowski for the racetracks and gin mills of L.A. Finally, Julia’s worth reading because she’s just a very good poet. You’ll always find things in her work that give a new slant on the writing life, or the war, religion, or the economy. Her work is a great bit of Americana, making poetic observation accessible for students, even children, and especially for people who had bad teachers and learned to dislike Poetry with a capital “P”. Much like Whitman made trascendentalism accessible to generations of readers, Julia makes poetic observation and belief profoundly accessible, available and fun.

Academia is moved frequently in the direction of funding, particularly round the conservative bend of the social gyre. So far, no one’s found a way to make poetry pay, financially. Most of the poets and presses struggle at the margin, living on little more than Hope. But these things come in cycles, and perhaps we’re headed back to a time where the expensive media-driven ways of thinking and feeling are going to seem less satisfactory to more people. You could see over 15,000 people attend a slam championship a few years ago. Poetry Slams have opened up the practice of poetry to a lot of new people, and poetry is becoming an art of practice today. That’s not bad. The rise of MFA programs is a good thing, and brings a lot of new people into a place of deep belief in poetry. Poetry has often represented a sort of gnostic worldview, and you can’t measure its value by numbers-otherwise, pro football would be the biggest literary event. So much of poetry’s history was made by the upper classes, court poets, etc… because they could afford to spend time thinking about things like literature. That doesn’t invalidate our tradition, but is an opportunity for the future. You could argue that there are more people involved in poetry today than ever before. But then, that sort of sidesteps the issue of whether and how poetry can matter.

Whitman saw poetry as providing the rudder to an American economic and social system that would otherwise be valueless, and would drift towards base human qualities. It is this great vision for a wise, sentient human future that makes poetry in America unsquashable. Read Whitman’s Democratic Vistas-it’s an eye opener. He was never the blind, pig-headed progenitor Pound portrayed him as. He was a visionary who saw all the human failings that made the ideal mission of poetry essential to American democracy. His insistence on that ideal, his confidence that it would be renewed generation after generation, make Whitman’s poetry an expression of the hope for mankind. This is the Parable of Matter. With every lost or sad soul that gives up the ghost, the importance of poetry for mankind becomes greater.

Maybe by that measure, today we’re further away from poetry or literary practice at the helm of determining values and human priorities in society. Maybe we have more souls than ever lost. Maybe media has usurped some the role of diviner, and that’s not a good thing. But think of this like Blake or Yeats saw the revolving of mores in society, the gyres. Perhaps the whole of our generation fell short under that wheel, or maybe we just have fewer champions of poetic vision that have been able to find the forefront. These things come around in circles, ebb and flow, and American democracy can still be the great invention, over the span of centuries. But it’s up to us, as poets and believers in futurity, to keep bringing that faith in human vision, of that secular open-minded eternity, to the forefront. Teaching and writing and mixing it up in the marketplace of ideas. Human progress is real, and eventually, society will follow a true direction because human aspirations flow, in this vein, towards the future.

The future may be in your lit class, right now, and just need a little nudge and understanding and open-minded guidance. Sometimes, you’ll see people treating poetry or lit like a joke, a leftover, a piebald child. But it’s important, what we’re doing, it’s the mission of Zeitgeist, it’s a beautiful child that has yet to reach its prime. And those new voices will make their own demands, cause their own raucous ruckus, get certain groups pissed off and turn the structure of things on its head. It’s going to be fun to watch, and it’s a reason to stay around, stay open, and keep an ear to the wind.

As David Lerner once wrote, the future of poetry is to do whatever the fuck it wants. Over the long haul, we don’t have to guide and direct it– it will guide and direct us. There’ll be more variety in medium, perhaps, in the future. Maybe today’s Dante, instead of writing about the circles of hell, will make a video game representation. Or maybe it’ll kick into the realm of politics, as America thickens into empire.

Poetry’s moving towards a more responsible, democratic representation of the human future, towards the divine average. We want a greater appreciation for the divinity in each of us. We’d like to see society overcome more of the base qualities of human nature, greed, jealousy, lying, rigid-thinking. Poetry can be key to that evolution, and will be. Lerner, referring to the zeitgeist, the spirit or genius of the times, used to say, the mission of poetry in the 21st century is to drive a cherry red Mercedes Benz into the heart of hell, and place a bet on God. Still today, that sounds just about right.